The Death of WCW: How Wrestling’s Biggest Rival Fell

The Rise of WCW

WCW started as Jim Crockett Promotions (JCP), a major regional territory within the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA). In 1988, media mogul Ted Turner purchased JCP and rebranded it as WCW, bringing it under the Turner Broadcasting umbrella. With national television exposure on TBS and significant financial backing, WCW became a major player in wrestling.

In the mid-1990s, WCW surged in popularity under the leadership of Eric Bischoff, who took bold risks to reshape the promotion. The introduction of Monday Nitro in 1995, directly competing with WWF’s Monday Night Raw, marked the beginning of the “Monday Night Wars.” WCW attracted top talent like Hulk Hogan, Randy Savage, and later, Kevin Nash and Scott Hall, who led the infamous New World Order (nWo) faction. Nitro’s edgier, more realistic storylines often crushed Raw in ratings, with WCW enjoying an 83-week winning streak.

The nWo: A Revolution That Changed Wrestling Forever

No discussion about WCW’s legacy is complete without delving into the phenomenon of the New World Order (nWo). Introduced in 1996, the nWo storyline was a turning point not just for WCW, but for professional wrestling as a whole.

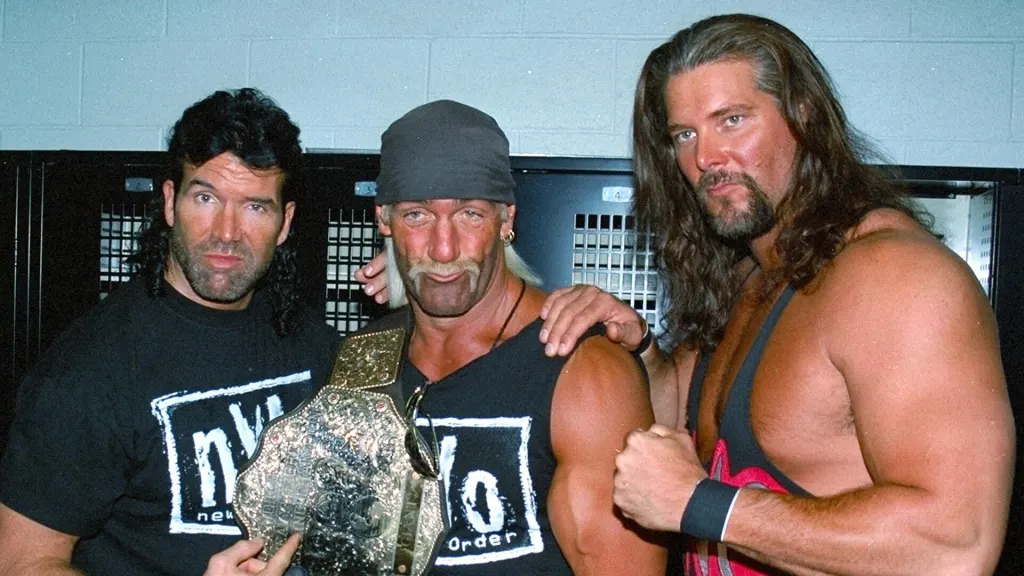

It all began at Bash at the Beach in July 1996, when Hulk Hogan shocked the world by turning heel for the first time in decades, joining Scott Hall (Razor Ramon) and Kevin Nash (Diesel) to form the nWo. Hogan’s betrayal of his “Real American” persona sent shockwaves through the wrestling world and marked the beginning of one of the most compelling storylines in wrestling history.

The nWo was portrayed as a renegade group intent on taking over WCW. They blurred the lines between fiction and reality, with Hall and Nash, former WWF stars, initially teasing that they were still working for WWF in a storyline invasion. The faction’s edgy, anti-hero personas resonated with fans of the 1990s, who were gravitating toward grittier and more realistic wrestling narratives.

Why the nWo Worked

The success of the nWo can be attributed to several factors:

- Star Power: Hogan, Hall, and Nash were some of the biggest names in wrestling, and their chemistry as a group was undeniable.

- Realism: The nWo’s tactics—interrupting matches, spray-painting their logo on wrestlers, and delivering cryptic promos—felt unpredictable and raw.

- Marketing: The black-and-white nWo logo became a cultural phenomenon, with merchandise sales skyrocketing. Fans packed arenas wearing nWo shirts, signaling their allegiance to the rebellious faction.

Too Much of a Good Thing

While the nWo initially revitalized WCW and dominated the Monday Night Wars, it also contributed to WCW’s downfall. The faction became too large, at one point featuring more than 50 members, diluting its original allure. Sub-factions like nWo Wolfpac and nWo Hollywood further confused the storyline.

Additionally, the nWo storyline overshadowed the rest of WCW, often relegating other talent and angles to the background. Fans grew tired of the group’s dominance and predictable “takeover” antics. By the late 1990s, the once-groundbreaking storyline felt stale, and WCW struggled to find a compelling follow-up.

The nWo’s Legacy

Despite its overexposure, the nWo remains one of wrestling’s most iconic storylines. It demonstrated the potential of well-executed storytelling to captivate audiences and cemented WCW’s place in history as a true competitor to WWE. Even after WCW’s demise, the nWo’s influence persisted. WWE incorporated the faction into its programming, including a memorable WrestleMania 18 moment where Hogan, Hall, and Nash clashed with WWE legends.

The nWo wasn’t just a faction—it was a movement. It changed the way wrestling was presented and marketed, ushering in a new era of mainstream popularity. Though WCW ultimately fell, the legacy of the nWo ensures it will always be remembered as one of the most revolutionary ideas in professional wrestling history.

The Cracks Begin to Show

Despite its initial dominance, WCW’s success began to unravel due to mismanagement, creative chaos, and financial irresponsibility.

- Creative Control Issues: Many top stars, including Hogan and Nash, had creative control clauses in their contracts, allowing them to veto storylines. This led to repetitive feuds and convoluted storylines, alienating fans.

- Bloated Roster: WCW signed an enormous number of wrestlers, many of whom rarely appeared on television. The payroll ballooned, but the returns diminished.

- The Fingerpoke of Doom: On January 4, 1999, WCW staged one of the most infamous moments in wrestling history. Kevin Nash, as WCW Champion, lay down for Hogan after a mere poke, “giving” him the title. Fans saw it as a slap in the face, marking a turning point in WCW’s fortunes.

- Failure to Build New Stars: While the WWF elevated talents like Stone Cold Steve Austin, The Rock, and Triple H, WCW relied heavily on aging stars, failing to develop younger wrestlers who could carry the promotion forward.

The AOL-Time Warner Merger

The corporate merger between AOL and Time Warner in 2000 was the nail in WCW’s coffin. New executives, disinterested in wrestling, deemed WCW a financial liability. Despite efforts to revitalize the brand under new creative direction, the company continued to hemorrhage money, losing millions annually.

The Final Episode

On March 26, 2001, WCW aired its final episode of Monday Nitro. The show, simulcast with WWF programming, was surreal. Vince McMahon appeared on WCW television to announce that he had purchased the company. Iconic WCW stars like Ric Flair and Sting wrestled their final matches under the WCW banner, closing an emotional chapter in wrestling history.

Legacy of WCW

Although WCW’s death marked the end of a major era, its impact on professional wrestling endures. The innovations of Nitro, the unpredictability of the nWo, and the sheer scale of the Monday Night Wars pushed wrestling to new heights. WWE’s dominance post-WCW’s fall has often been attributed to lessons learned during their rivalry.

Today, WCW’s legacy lives on through nostalgia, WWE’s vast archive of WCW footage on Peacock and the WWE Network, and the resurgence of competition with promotions like AEW—ironically founded by a lifelong WCW fan, Tony Khan.

The story of WCW serves as both an inspiration and a cautionary tale. It was proof that wrestling could thrive with bold vision and ambition, but it was also a reminder that mismanagement and hubris can bring down even the mightiest of empires.

News Writer. Living in Tasmania Dave is a lifelong wrestling fan, formerly working for Mix It Up Radio’s Wrestling Asylum Radio program, and Wide Bay Pro Wrestling working backstage and writing articles. Podcaster with 15 years of journalism experience across different sports mostly AFL and professional wrestling, photographer for local footy in Tasmania.